I Work For Bill

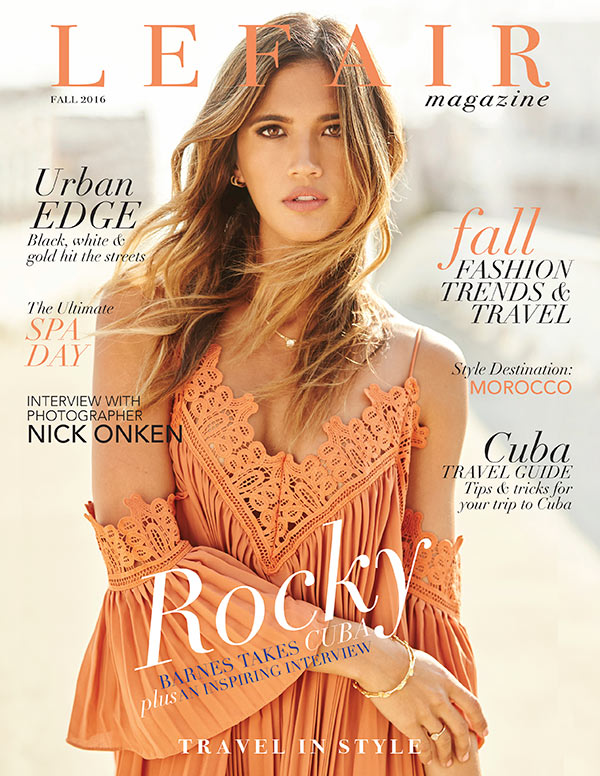

LEFAIR

Fall Issue – 2016

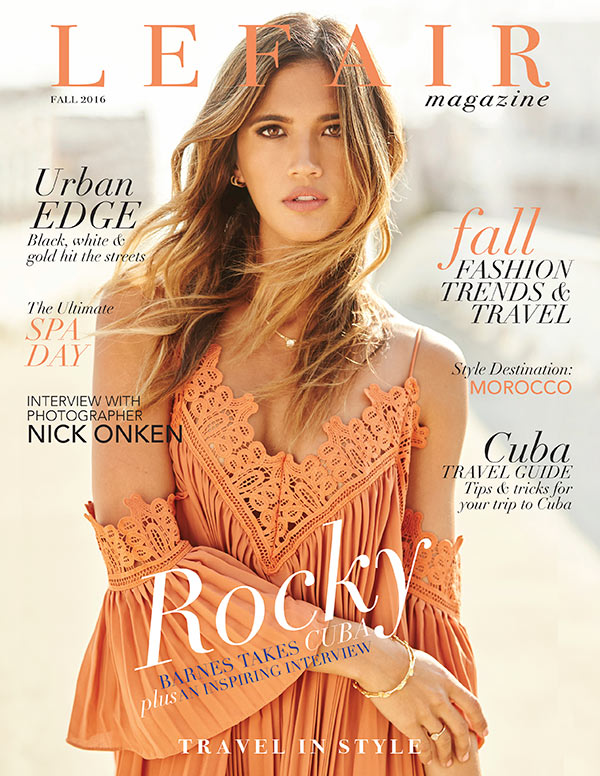

Afrojack Afrojack @Afrojack Photographer Collin Stark @collinstark Writer Julianne Zigos @juliedee59 Creative Director Tracy Kahn @tracykahn Wardrobe Stylist Desiree Morales @desireemorales Assistant Stylists Natasha Fomina... Read More

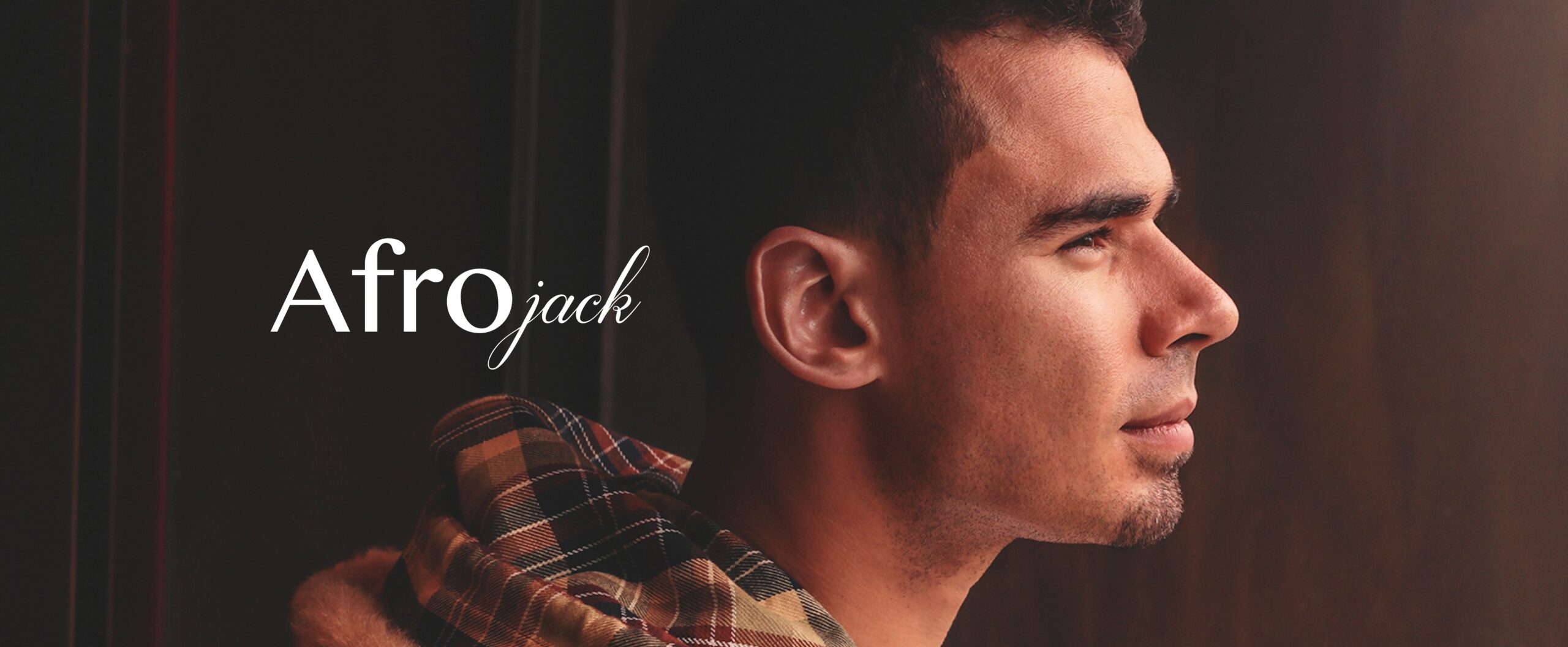

Photography: Tracy Kahn @tracykahnModel: Kari Riley Stylist: Ilaria de PlanoVideographer: Ben Shani and Matt MastrapaMakeup and Hair: Samantha Chapman... Read More

The house is grand but warm and full of sunlight. It is the perfect day to shoot. Leftover floral arrangements... Read More

Writer Madeline Rosene @madelinerosene Photographed by Kat Harris @thekatharris LEFAIR Fall Issue – 2016 . Creative junkie, Nick Onken, and I met at Soho... Read More

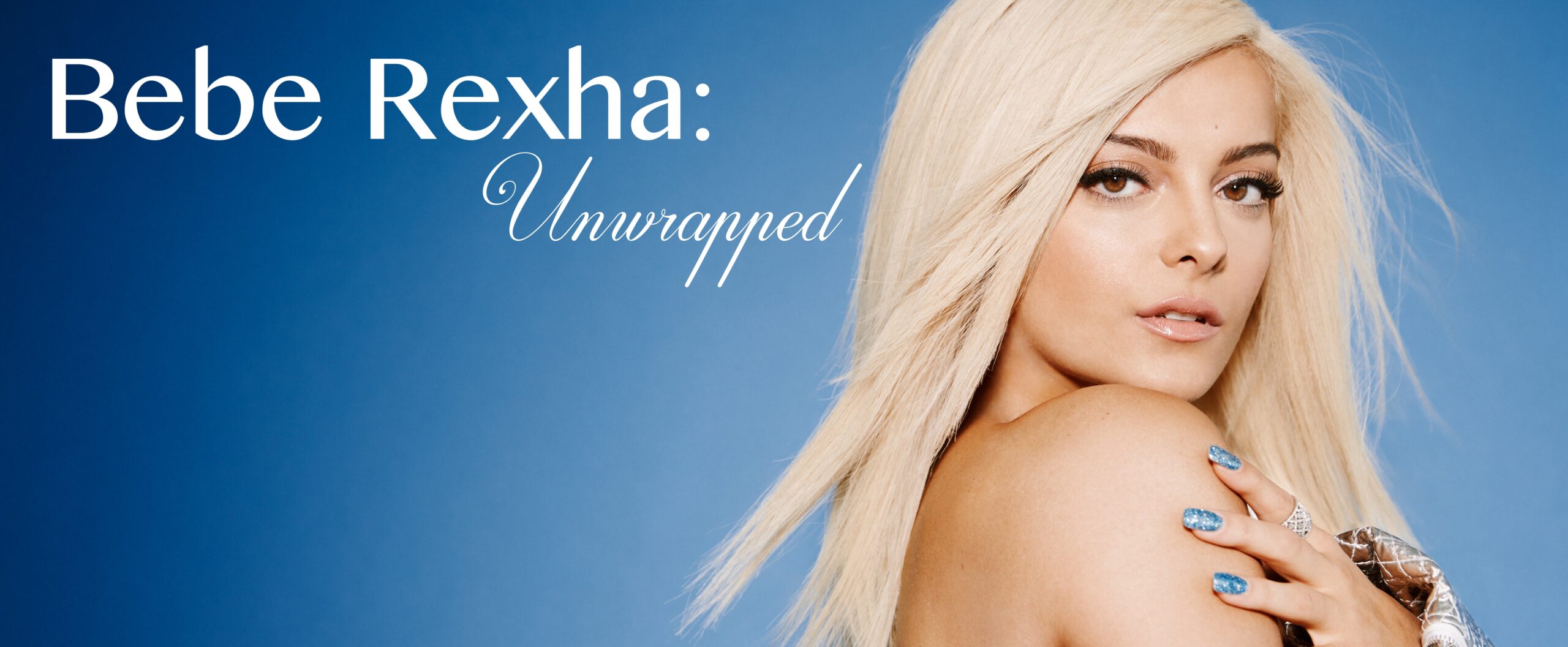

Writer Madeline Rosene @madelinerosene Photographer Kate sZatmari @kateszatmari Creative Director Tracy Kahn @tracykahn Wardrobe Stylists Desiree Morales @desireemorales and Cassandra Dittmer @cdittmer Makeup Artist... Read More

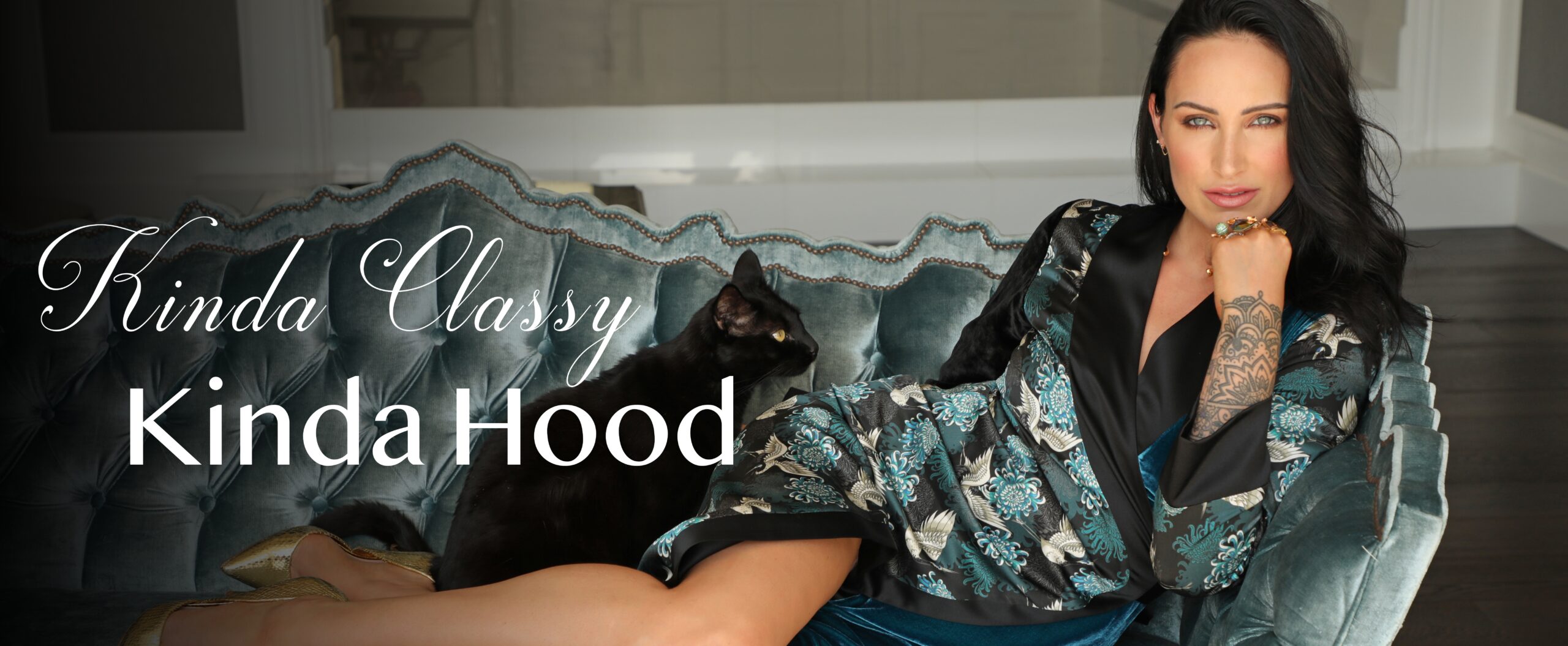

Sam Blacky @samblacky Photographer Tracy Kahn @tracykahn Writer & Wardrobe Stylist Madeline Rosene @madelinerosene Hair & Makeup Artist Kendell Cotta @kendellcotta Drone Videographer... Read More

Victoria Justice @victoriajustice Maddy Grace @themadgrace Victoria Justice was visiting her parents and half sister, Maddy Grace in a house covered... Read More

The way the sun seeped into the LEFAIR North Hollywood loft and bounced off of the white walls would... Read More

Photographer and Videographer Steven Lyon @steven_lyon Writer Katharina Kowalewski @katharinaishere Wardrobe Stylist Randall Truitner @randian Assistant Stylist Yvonne Reddy @yvonnereddy Hair Artist Trace... Read More

Writer: Jaye Younkin Videographer: Josh Goodell A line of people of all ages, races, and talents wrapped around the Pasadena Convention... Read More

Leave a Reply